I recently found this old paper from my senior year of college sitting in my drafts folder — a very cut-and-dry analysis of a particular Medieval stained glass window at the Cloisters Museum in New York. I like it not because it’s particularly interesting, but because I recall writing it in one night, feeling as though I’d mastered the academic essay form: boy did I have a long way to go. (ELP, 2015)

As with many objects surviving from medieval times, the Theodosius Arriving at Ephesus stained glass panel (Fig. 1, Cloisters Museum:1980.263.4) has a history that is nearly as interesting as the artifact itself. With so many pieces lost over the centuries, and so many pieces added, there is an imaginative gap that must be leapt if we are to understand this artifact within the setting and context of the world and people that created it. Beginning with an analysis of the Theodosius panel in its current state, I will move back in time to imagine what this piece was like in its original condition as part of a greater stained glass window, and discuss art historian Michael Cothren’s hypothesis regarding the reasoning behind the choice of this Christian myth for the Cathedral of Rouen.

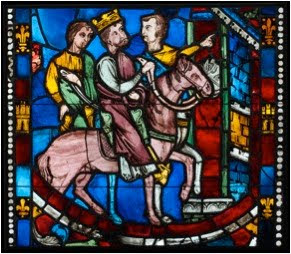

The Theodosius panel is 25 x 28¼ inches, and has been dated with unusual precision to 1200-1204.1 In it, three figures are depicted riding horses towards a portal or door of some sort. The central figure, wearing a golden yellow crown with a brownish purple costume rides a that is somewhere between tan and pink in color. A man to the right of the crowned figure points to the architectural space, represented by a wall of alternating blue and yellow bricks alongside a door formed by thin, light green supports and a white threshold. He points at this door, and his horse has already pushed his nose through. The horse, the gesture of this man, and the gaze of the crowned figure all create a sense of movement that leads our eye rightward, towards the portal and beyond. If we step back from the Theodosius panel, and imagine it as part of a greater composition, we can see how this rightward motion moves our eye across to the adjacent panel of stained glass, in which the next scene of the story would be depicted. The three figures are layered atop each other very closely in a way that does not provide much illusion of depth, however the illusion of depth is not something the medieval master artisan was striving for, nor does stained glass as a medium lend itself to the representation of three-dimensional spaces.

For the purpose of depth, the nose of the hose poking through the portal is enough to indicate the narrative motion of the story. Rather than depth, the strength of stained glass lies in color and radiance. The majority of this panel is occupied by vibrant blues, deep reds, and golden yellows. A number of secondary colors illuminate smaller areas: green (on cloak of the leftmost rider, on the vertical elements of the portal, and on the trappings of the king’s horse), light blue (for the middle horse, and the brickwork); white (on the backmost horse, and several of the architectural elements; and flesh tones, which vary slightly in the case of each figure.

Perhaps the most baffling aspect of the composition of this image is the surrounding border, which seems at first glance a bit of a hodgepodge. On either side of the panel there is a vertical line of white dots, like a string of pearls; inside of that is a framing line of blue and red rectangles, regularly interrupted by golden yellow images of castles and fleurs-de-lys.

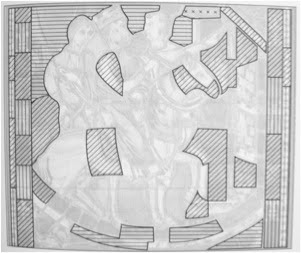

Fig. 3: Cothren’s hypothesis as to the full composition of the Theodosius narrative within the stained glass window. 17 is where the Theodosius in question was probably located.

The pearls are thus mees the story further alonant to make the stained glass panel more appealing to the sensibilities of 20th century collectors, making the artifact both easier to handle and easier to sell. Having removed these later additions, it is possible to imagine the Theodosius panel as it existed as one-fourth a medallion within a tall Gothic window (Fig. 3). Each individual panel thus progressg from beginning to conclusion. In order to place the Theodosius panel properly within the framework of this dismantled window, we must first look at the story it is depicting.

The Theodosius panel stands by itself as a masterpiece of stained glass. The vibrant colors, the composition, the control of line and movement, all carefully planned and executed, is beautiful and valuable in and of itself. Yet it is the history that brings it to life: the chance fires and shifts in political power that led to its creation; the luck that allowed it to survive political shift to French rule despite its English agenda; the reworking and reformation of it into new windows; and finally, the years of being passed among different owners and dealers. All this provenance is obscured from the casual viewer sauntering through the Cloisters Museum, yet the evidence of it is present. It is this history that adds dimension to what otherwise would simply be a well worked piece of artisanship severed from its original body, removed from its setting and divorced from its significant political and historical import.

Notes

1 Michael W. Cothren, “The Seven Sleepers and the Seven Kneelers: Prolegomena to a Study of the “Belles Verrieres” of the Cathedral of Rouen,” Gesta, Vol. 25, No. 2, p. 209. (International Center of Medieval Art, 1986) .

The Metropolitan Corpus Vitrearum more liberally dates the Theodosius between 1200-1210.

Jane Hayward, Mary B. Shepard, and Cynthia Clark, English and French Medieval Stained Glass in the Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Corpus vitrearum, vol. I, (New York, N.Y: Harvey Miller Publishers and the Metropolitan Museum of Art for American Corpus Vitrearum, Inc, 2003) p. 101.

1 Eugene-Emmanuel Violett-le-Duc, trans. Francis P. Smith, Mediaeval Stained Glass, (Atlanta: Lullwater Press, 1946) p. 13.

“An opaque painting rightfully should define various planes, and even when it consists of a single figure against a flat background, the artist attempts to indicate three dimensions in his figure. If the early painters did not always attain this result, it was nevertheless their goal. To transpose this quality of the opaque painting to a translucent medium, is wrong. The true ideal of translucent painting is that the design should express as energetically as possible a beautiful harmony of colors, which, when realized, is all that can be desired.”

1 Cothren, 203.

2 Cothren, 205.

3 I recognize that The Golden Legend was written well after the creation of this stained glass panel. Nonetheless, it serves as the closest authority on early Christian mythology for the purposes of this paper.

4 Paraphrased from The Golden Legend.

5 Cothren, 208.

6 To this day, Edward is the official Saint of royalty.

7 Qtd in Cothren, 222: “quod fratrum et amicorum nostrorum sepultura nobis venerabilem in perpetuum

commendat.” trans., “the Cathedral holds in venerable perpetuity the graves of our brothers and our friends.”

8 We see a similar tactic employed in the 18th centruy by Cathrine II in Saint Petersburg, whose enormous artistic propaganda campaigns aimed to prove her bloodline was directly Peter the Great, though not a drop of it flowed through her German veins. The Bronze Horseman is perhaps the best example.

9 Cothren, 209-212.

Bibliography

Viollet-le-Duc, Eugène-Emmanuel, trans. Francis P. Smith. Mediaeval Stained Glass. Atlanta: Printed at the Lullwater press, 1946.

Categories: Art History, Christianity, History, Medieval, Mythology, Short Essays, Stained Glass, Uncategorized, Vassar